Author: Hans Bax

Navigating the public procurement process for health care in the EU is a complex task that involves multiple stakeholders who often have differing perspectives and local specificities. While parties may be seeking a joint procurement experience that is based on the fundamental principle of ‘value’, the term can be interpreted broadly depending on the player and the locality. In my view, solutions must therefore be sought to safeguard local decision-making while supporting the European Commission’s push for greater cross-border collaboration.

The partners of the European Wide Innovative Procurement of Health Innovation (EURIPHI) project acknowledge that there will be a variety of differences between participants (e.g., procurers, health care providers, etc.) ranging from language to local preferences, thus creating obstacles along the way. Full collaboration during the preparatory phase of a cross-border procurement project can lead to a better outcome while addressing common unmet needs for the parties involved. However, from my perspective, executing a full joint tender until the very end is simply not feasible.

Therefore, the question is not if, but when, do we go our separate ways?

The EURIPHI partners have developed three recommended cross-border procurement collaborative models that can be applied to facilitate the tender process. Before exploring these, it is helpful to look briefly at the framework that underpins EU health care procurement decisions and the potential bottlenecks that can occur.

EU public procurement framework

European Directive 2014/24/EU governs the procurement and tender process of public authorities including (most) health care procurement organizations across Europe in order to award contracts for the purchase of public works, goods, and services in a transparent, fair, and competitive manner.

The aim is to ensure the free movement of such supplies, services, and works within the EU by creating a more flexible, modernized public procurement process. Although the Directive encourages cross-border collaboration and joint procurement, it also recognizes that some sectors, including health care, require special consideration. The context in which health care services are delivered across Europe – as reflected by the below text from the Directive – provides a deeper understanding of why joint procurement can become problematic, and why there is a need to safeguard local decision making.

“Certain categories of services continue by their very nature to have a limited cross-border dimension…such as certain social, health and educational services. Those services are provided within a particular context that varies widely amongst Member States, due to different cultural traditions…Member States should be given wide discretion to organise the choice of the service providers in the way they consider most appropriate.”

The flexibility that was explicitly built into the legislation regarding the provision of health care services has a knock-on effect for the procurement process because health policy falls within the remit of national authorities. It is not surprising, then, that a significant impediment to cross-border collaboration in health care procurement is the Member States’ transpositions of the Directive into their own national legal frameworks.

Other demand and supply side bottlenecks

To those parties in health care having a common interest in responding to their unmet needs by procuring innovative and value-generating solutions, cross-border procurement collaboration can render all phases of the public procurement process more efficient and effective.

However, in addition to varying national legal frameworks, other differences between participants and bottlenecks on the demand and supply side can arise when participating in a cross-border project. These include:

- Finding common ground on exact local requirements

- Structure of health care provision and organizational set-ups

- Health care payment and reimbursement models

- Language and business culture

- Differences in local product and solution offerings by medtech suppliers

- Limited supply and implementation capacity to support full-scale cross-border projects (especially by start-ups/scale-ups and SMEs)

- SMEs, having local development and offering of innovations, not covering on a European level, thus hampering participation in EU-wide public procurement tenders

- “Stacking” of individual buying volumes by procurement organizations, creating excessive demand volume, endangering competition, and increasing the probability of single-bid tenders

Given the context of public procurement and these issues, parties involved in a collaborative project will have to identify to what point during the full preparatory tender and tender process it is appropriate to closely cooperate and when to go separate ways.

Safeguarding local decision making: three models

During the preparatory phase, parties work very closely together, exchanging knowledge and experience. In general, they recognize the added value of cooperation in the identification and prioritization of common unmet needs, the allocation of resources to meet these unmet needs, the execution of joint open market consultations to assess market readiness, and the joint drafting of solution requirements and procurement/tender specifications. Therefore, full collaboration in this preparatory phase is considered a priority and, in my opinion, provides an excellent basis for the subsequent execution of the tender phase.

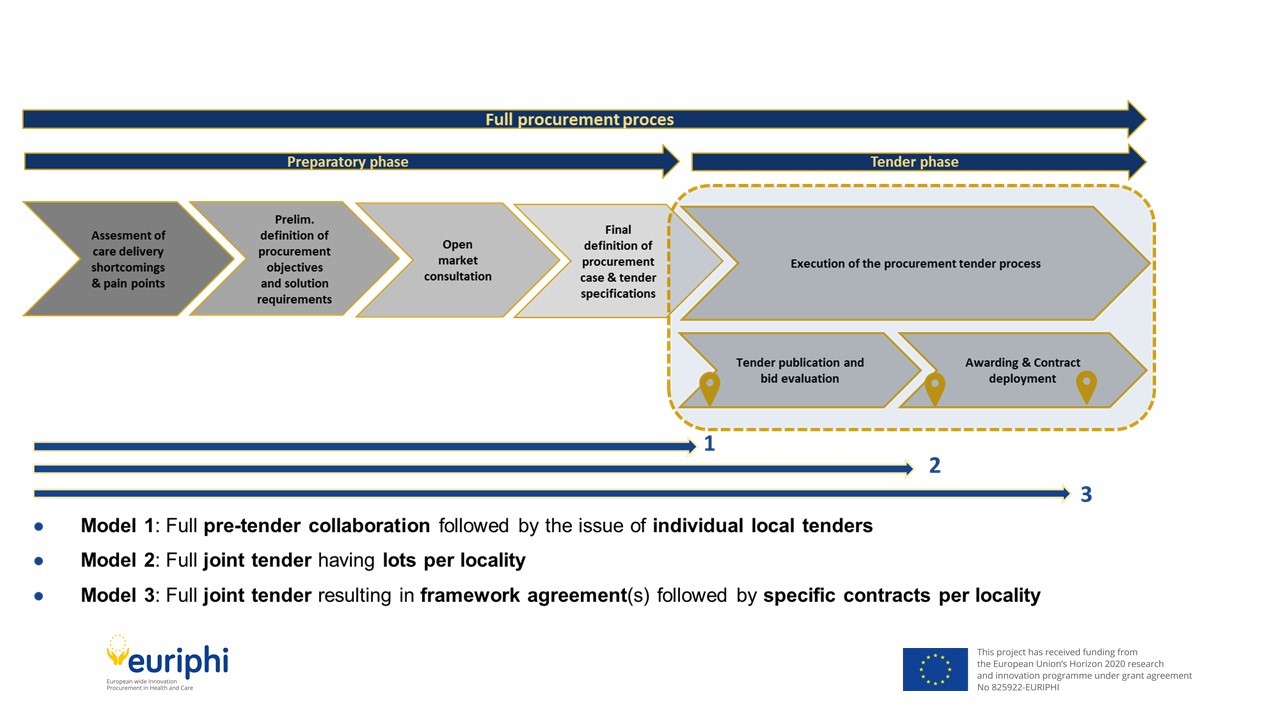

The tender phase comprises the actual execution of the tender process. Considering the challenges on demand/supply side and the consecutive need to manage local refinements (e.g., specific local needs and requirements), EURIPHI partners have identified the following three modalities as depicted in the below diagram.

One of these should be applied to safeguard localized decision-making depending on the level of differences identified in the preparatory phase:

- Full preparatory phase collaboration, subsequent issue of individual tenders (Model 1)

- Full preparatory phase collaboration, subsequent issue of a joint tender having individual lots to be awarded by each participating party (Model 2)

- Full preparatory phase collaboration, subsequent issue of a joint tender resulting in the awarding of a framework agreement to be implemented locally using specific contracts (call-offs) by each participating party (Model 3)

When there are numerous differences between participants due to local requirements, etc., I believe it is best to use Model 1; however, where very few differences are expected, Model 3 may be the most suitable option.

Benefits of full preparatory phase collaboration

It is clear to me that full collaboration in the preparatory phase, in addition to applying one of the above three cross-border collaborative procurement models to safeguard local decision making, will have positive consequences for both health systems and patients.

Health systems will benefit from information sharing, knowledge exchange, and economies of scale, among other things. Patients, for example those who suffer from rare diseases or those who are affected by a pandemic, will have greater access to innovative health care solutions, which in turn will lead to better care and improved clinical outcomes.

It is important to note that this may not necessarily speed up the procurement process, but it will result in a better solution. As the saying goes: “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to far, go together.”

Hans Bax is holding over 20 years of international experience in procurement and supply chain management, especially in health care provider organisations. Hans has been the Procurement Director of the University Medical Center in Groningen (Netherlands) for over 15 years and subsequently has been representing GDEKK, a Germany-based Group Procurement Organisation, serving hospitals in both Germany, Austria and the Netherlands.

Starting 2019 Hans is supporting the Value-Based Procurement Community of Practice and participating in the European EURIPHI project on the development and adoption of (MEAT) Value Based Procurement in healthcare. In addition, Hans is a senior lecturer on public procurement and tender management at NEVI, the Dutch Association for Purchasing Management.